More than half of Americans have taken money out of their retirement savings, including 401(k) accounts, early. This has led to them paying billions of dollars in penalties to the IRS every year. Unfortunately, taking money out early can hurt how much you save for retirement in the long run. This is even more true if you don’t have a plan to put the money back.

Economists call taking money out before retirement “leakage.” It’s a big reason why many people don’t save enough for when they retire. The IRS only lets you take money from your 401(k) without taxes and penalties in a few special cases covered by “ hardship distributions” that crop up if you’re in a really tough spot financially. Otherwise, if you take money out too soon, you have to pay a big 10% penalty on the amount, plus any taxes you owe.

Because of these taxes and penalties, most money experts say you shouldn’t take money out of your 401(k) early unless you really have to.

But there’s a group that has found a way to get around this usual advice. The community is commonly referred to as FIRE, which stands for Financial Independence, Retire Early. They are hell-bent on being financially independent and retiring early.

The way they take money out of retirement funds is different. If you’re thinking about taking money out of your retirement funds early, it’s good to know what they do. This knowledge can help you plan better, minimize and/or penalties, and keep your retirement money safe.

Surveys show that more and more Americans are taking money out of their 401(k)s early, even though it means paying penalties and missing out on the chance for their savings to grow. Interestingly, this isn’t just happening with one group of people; it’s across different ages and income levels.

It’s even happening with younger folks. After the pandemic, a 2021 study found that Gen Z, the youngest adult generation, was taking money out of their retirement accounts early more often than older people.

There’s been a rise in specific types of withdrawals, which the IRS monitors. This helps us understand the reasons behind people’s choice to withdraw early.

The most common trigger for early withdrawal remains a job change. A 2023 study showed that 41% of 401(k) account holders withdraw at least some funds from their accounts when changing jobs instead of completing a rollover into an IRA or new 401(k) plan. The same survey showed most of those cashing out withdraw the entirety of their 401(k) balance.

People also often take money out of their 401(k) accounts for other reasons.

One of the increases has been in withdrawals for “hardship.” The IRS lets people take money out of their 401(k) in cases of urgent and big financial needs, like for some medical bills or funeral costs. The number of folks making these “hardship withdrawals” jumped by 36% from the second quarter of 2022 compared to the same period in 2023, according to data from Bank of America.

This means that many Americans are struggling with money problems, causing them to use their retirement savings.

Many experts say you should try every other option first, like getting a loan or using your emergency funds.

Also, sometimes people just want to take money from their 401(k) to keep their standard of living after losing some income, to buy something big like a boat or a car, or to have more money before they retire. Even though it’s not the best financial decision, they decide to pay the penalty to have some cash available.

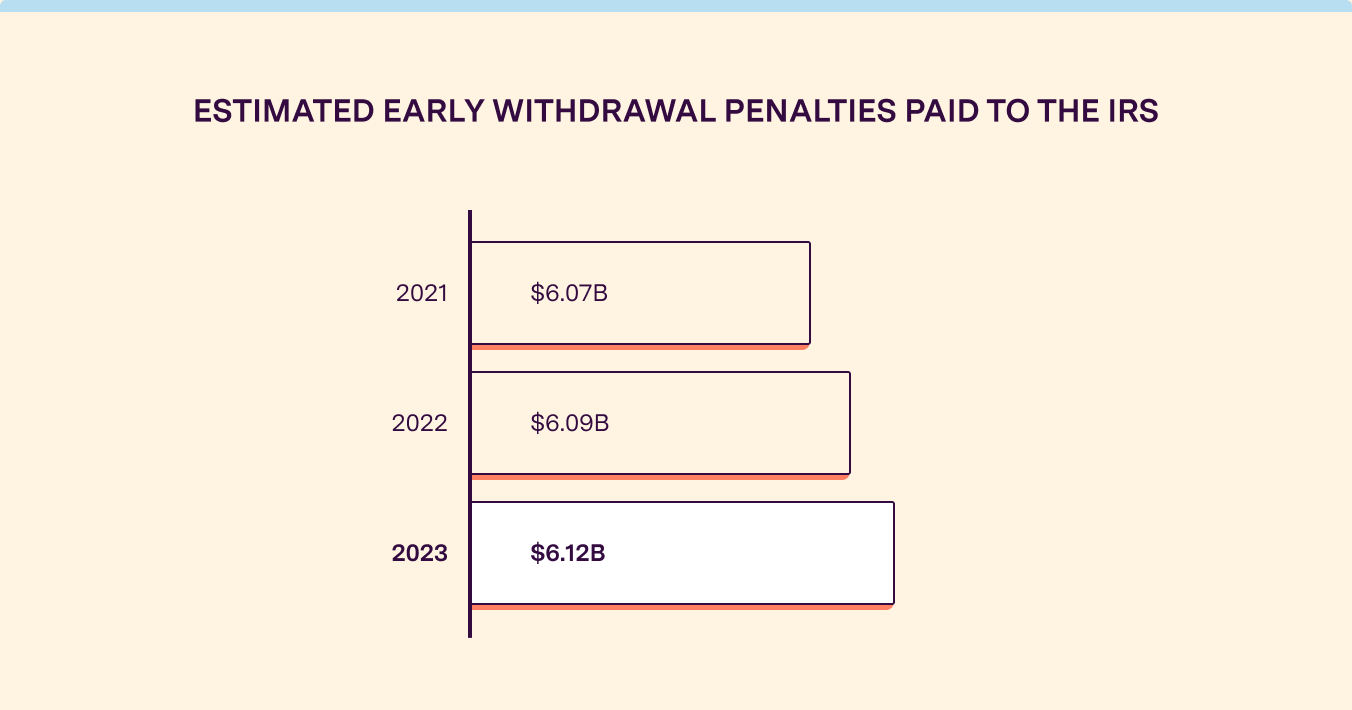

We estimate these withdrawals will cost Americans $6.12 billion in penalties to the IRS in 2023.1

The FIRE movement is all about seriously cutting costs, earning more, and investing a lot. Some followers aim to retire way earlier than the usual 60 or 65 years old, even in their 30s and 40s.

They try to save up to 70% of what they make. They also invest in different accounts, like Roth IRAs, which have tax benefits, and regular investment accounts.

Two big rules in FIRE are the 25x Rule and the 4% Rule. The first one says to save 25 times your yearly expenses to retire comfortably. The second one says you can take out 4% of your savings in the first year of retirement, and the same percentage later on, without running out of money. But you’ll need to adjust for things like inflation and how well your investments are doing.

In the FIRE community, there’s debate about how much to put in 401(k)s, especially if you want to retire early. The usual advice is to put in as much as you can each year, get any employer matching, and max out contributions to accounts like a Roth IRA, which lets you take out money earlier more easily.

For FIRE folks, managing a 401(k) means really focusing on not paying too much in fees, avoiding bad investment choices, and having the right mix of investments. These things can really affect how much your savings grow.

Even if they want to retire early, FIRE people agree with the common advice to not take money out of your 401(k). They really don’t like penalties, fees, and extra taxes. They know a lot about IRS rules.

But many FIRE followers do retire way before 59½ years old. To make their money last and follow the 4% rule, they need to get to their 401(k) money early.

How do they do it without paying big penalties or taxes?

They use two methods: the Roth Conversion Ladder and 72(t) Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP).

Let’s break them down.

Roth IRAs let people over 59½ take out their original contributions and any earnings without paying taxes.

But Roth IRAs also have a unique rule that appeals to FIRE devotees. The rules say that contributions can be withdrawn at any age, without taxes or penalties (not so earnings, which are subject to taxes and the dreaded 10% penalty until age 59½).

The hitch is that contributions must be held in the account for at least five years before the amounts can be withdrawn tax- and penalty-free.

Enter the Roth Conversion Ladder.

FIRE enthusiasts commonly roll over 401(k) funds into traditional IRAs, then convert a portion of the funds each year into a Roth IRA. This is a taxable event, so FIRE types tend to convert only the bare minimum they think they will need in the future. Each conversion has its own five-year waiting period.

If you do this every year, you’re making a “ladder” of conversions. After the first five years, you’ll have a chunk converted and ready to go every single year.

When you retire, any earnings and contributions you didn’t use are still in the IRA.

The second method is called 72(t) Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP). It’s a rule in the tax code that lets you take money out of your traditional IRA and 401(k) early without penalties. The rule states that you have to take out about the same amount of money at least once a year for five years or until you’re 59½, whichever is longer.

You won’t pay the early withdrawal penalty on these withdrawals, but you usually still have to pay income taxes on them.

The IRS has rules on how much you can take out and how to figure out the payments. There’s some wiggle room in how you calculate them. They’re called “substantially equal” payments because the amount can change a bit, like to keep up with rising costs.

People who like the FIRE approach often move their 401(k) money into IRAs and then take 72(t) SEPP payments from these IRAs. For more flexibility, they might use several IRAs and start the 72(t) payments at different times. This way, they can adjust how much money they get over time.

Using these strategies, 72(t) SEPP and the Roth IRA Conversion Ladder, requires a lot of planning.

The Roth IRA Conversion Ladder makes you think about what money you’ll need in five years, which can be tough.

72(t) SEPP lets you get money sooner, but it has strict rules. Planning is key because if you don’t follow the rules, you could face penalties and owe back taxes.

No matter what, when you use these strategies, make sure you still have enough money in your retirement accounts for when you’re older than 59½.

It’s really important to understand these strategies well to use them right. Thinking of them as different ways of traveling might help.

Picture the 72(t) SEPP as a train that’s always on time and stops regularly.

The train starts when you want, but once you choose this way, you have to follow the IRS’s schedule. This train, like your retirement account, stops at set times, even if you don’t need the money then.

This is like a “set-it-and-forget-it” plan. After you start, you can’t change the times, stop the train, or skip a stop. Doing that brings penalties. It’s a long trip – you keep going for five years or until you’re 59½, whichever takes longer. So, if you start at 40, you’re on this train for 19½ more years.

The Roth Conversion Ladder is more like planning a road trip five years ahead. You decide where to go and when to stop, which means when and how much money you take out. It’s different from the train because there aren’t fixed stops. But you can only do what you planned for five years ago. It’s like setting your GPS, with all your stops and how long you’ll stay, five years in advance.

You also need to plan for the next five years, like making sure you have enough money for your daily expenses and the taxes when you switch to Roth.

The FIRE movement is all about seriously cutting costs, earning more, and investing a lot. Some followers aim to retire way earlier than the usual 60 or 65 years old, even in their 30s and 40s.

On the internet, FIRE blogs and discussion groups are full of tips about rolling over 401(k)s and retiring early. Reddit, with channels like r/Fire/ and r/financialindependence, and blogs such as Mr. Money Mustache, also have helpful information.

To make these ideas easier to understand, we’ve come up with a simple example.

Let’s talk about Riley and Jordan, a made-up couple who like FIRE ideas.

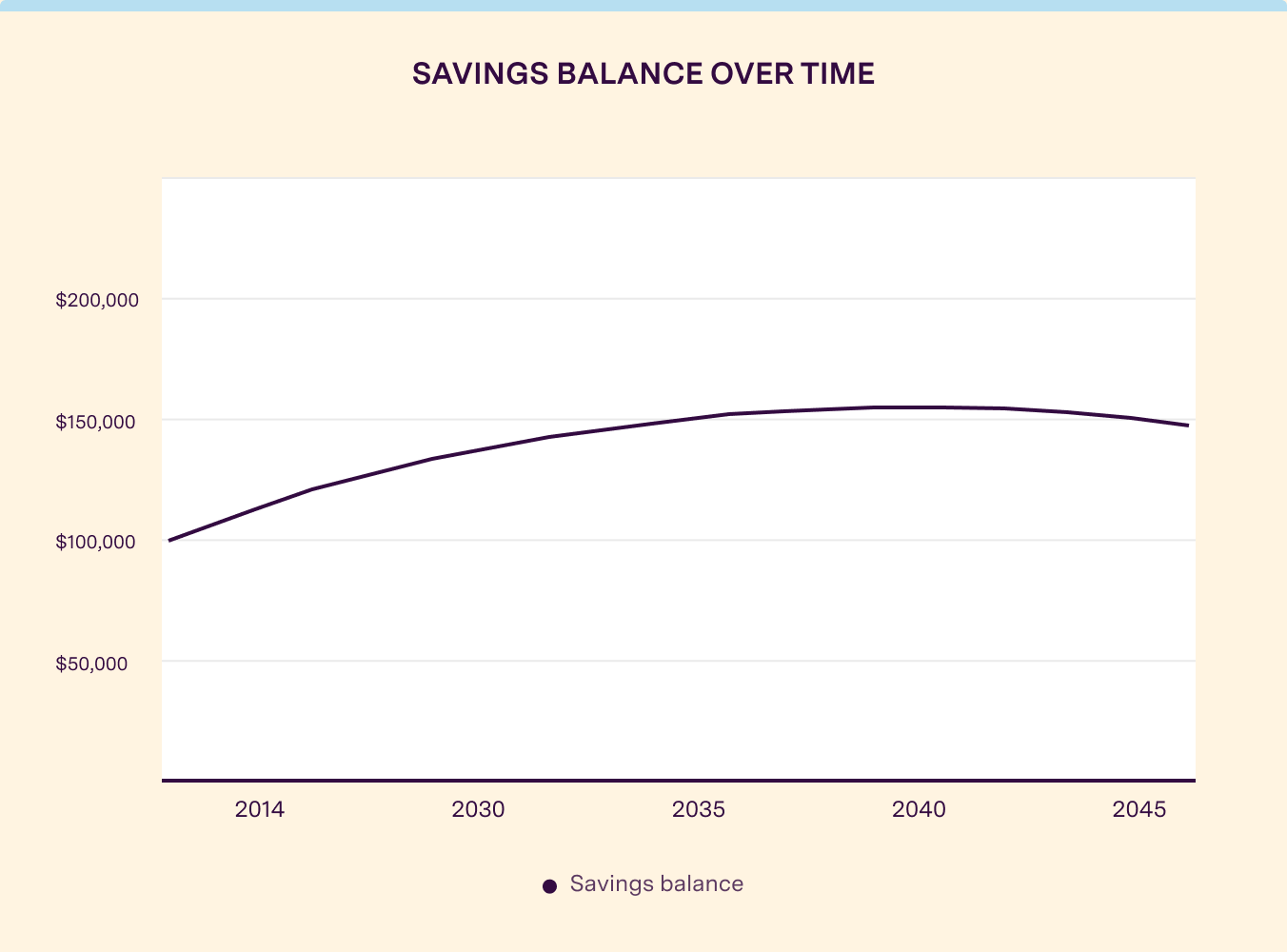

They’re programmers in their late thirties. In 2023, they find out they have $100,000 in their 401(k) accounts. Instead of following usual money advice, they want to use this money to add to their income. Their plan is to start when they turn 40, which is in three years.

After moving their 401(k) money into traditional IRAs, they choose to use a mix of different tactics:

They project an average 6% growth in their accounts from investment gains, and we will assume this pans out.

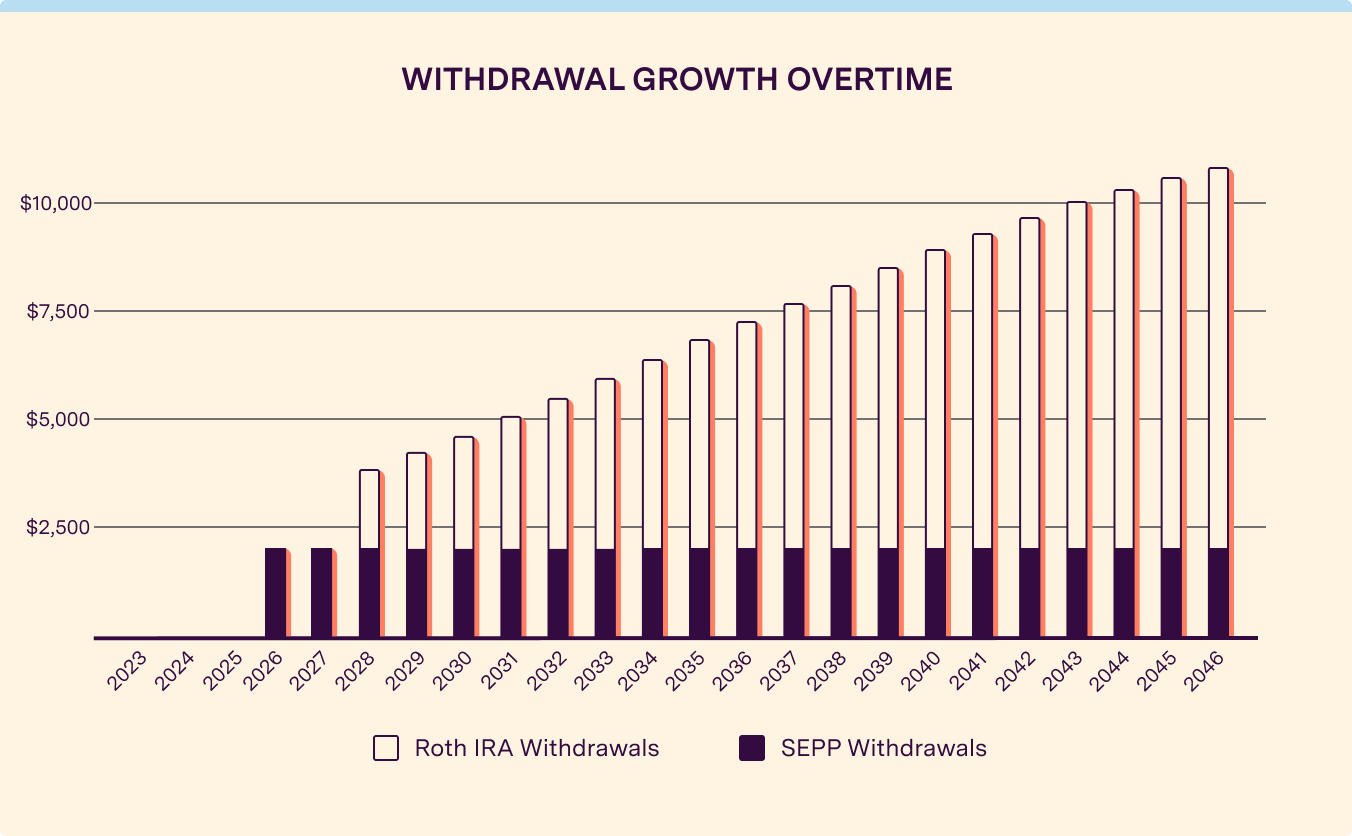

The charts and table below visualize their withdrawals and the evolution of their total savings.

| Year | Event | Withdrawal Amount in Year | Withdrawals as % of 2026 Balances | Approx. Savings Balance at Year-End |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026 | Supplemental income starts. | $2,000 | 1.7% | $124,128 |

| 2028 | Roth Conversion Ladder kicks in | $3,942 | 3.3% | $133,044 |

| 2031 | 4% rule is breached | $5,141 | 4.3% | $142,540 |

| 2045 | Final year, the couple reaches retirement the next year. | $10,577 | 8.9% | $146,902 |

Table 1: Riley and Jordan’s FIRE-inspired early use of 401(k) funds for income supplementation

Jordan and Riley have an aggressive plan. It breaks the 4% rule as they get closer to retirement age, reaching 8.9% of their initial 401(k) balance in 2045, right before they turn 59.5.

Yet, their savings don’t run out.

By 60, even after taking out nearly $150,000 over 20 years, they’ll still have about $147,000 left. This is thanks to their investments growing, their small early withdrawals, and avoiding penalties and extra taxes (thanks to the Roth Conversion Ladder and 72(t) SEPP). Of course, they could have had more growth if they hadn’t touched their funds.

But Jordan and Riley plan to keep working. This example doesn’t even count any other income or retirement accounts. They’re using FIRE and their 401(k)s as a safety net for their switch to freelance work. Their approach is unusual, but it’s part of a well-thought-out financial plan.

In 2046, they will reach the official retirement age. Then, they can stop the SEPP payments. They can use any Roth IRA earnings without taxes or penalties. They can also choose almost any withdrawal plan they want.

Their story shows the financial benefits and flexibility you can get with FIRE strategies. It also shows how these strategies can fit different financial goals and situations.

The FIRE movement, which supports quitting work early, shows how work and retirement are becoming less distinct from each other.

It also changes how we think about money. In FIRE, people are encouraged to take charge of their retirement, explore different methods, and use every part of the tax code to their benefit.

But even with FIRE, you can’t ignore things like time, rising costs, and life’s unexpected challenges.

Fans of FIRE have to think about getting to their retirement money early while making sure it lasts. Retiring early means needing money for many more years. To give an idea, $1 in 1973 is like $6.93 today, so you’ll need a lot more in the future.

They also need to plan carefully to avoid penalties and taxes that could decrease their savings.

Since many Americans struggle with basic 401(k) management, it’s better to get the basics right before trying FIRE. For instance, too many people cash out their 401(k)s when they leave a job. If you’re thinking about these ideas, talking to a financial or tax advisor first is smart.

Lots of Americans aren’t saving enough or have big credit card debt. These problems need solving before you can make the most of a 401(k).

On the other hand, FIRE gives good basic advice like avoiding high fees and getting the most from things like employer matches and Roth IRAs. Also, many don’t know they can use their 401(k)s early following IRS rules. This lack of knowledge could mean missing out for those who could really use early access, as long as it’s done wisely.

Handling a 401(k) with life’s ups and downs needs careful planning and a deep understanding of retirement accounts. It’s about balancing what you need now with your goals for the future. The goal isn’t just to retire early like in FIRE, but to have financial security throughout your working and retirement years.

1 Source is a conservative estimate based on 2019 IRS numbers and 2015 to 2019 average growth rate in those numbers also from the IRS. The methodology takes the average percentage growth in USD penalties paid to the IRS on early withdrawals from retirement accounts, from 2015 to 2019, and applies to 2019 to approximate post-COVID 2021 year end total, 2022, 2023, etc, while eliminating the outlier of COVID when many penalties were waived.