Background

401(k)s remain a key part of the retirement savings of many private sector workers. At the end of 2022, Americans had accumulated almost $7 trillion of assets in 401(k) accounts. Over 66% of private sector workers now have access to defined contribution retirement benefits through an employer, and encouragingly this number continues to grow.

There are many benefits of these employer-sponsored retirement accounts. Employers can “nudge” their employees to use them and even incentivize additional saving through employer matches. Our 401(k) contributions come directly out of our paychecks, leading to automated saving and highly effective dollar-cost averaging.

Unfortunately, though, 401(k) savings do not automatically travel with us as we change jobs. Instead, job-changers who have a 401(k) are presented with a series of choices when transitioning:

These choices can be confusing. Unsurprisingly, many Americans defer the decision and leave their 401(k) behind to deal with later. The result is that job switchers can end up with a string of 401(k) accounts tied to former employers, each with different fees, asset allocations, and custodians. This scattering of accounts makes it hard to ensure that an individual’s retirement savings are compounding at the rate that they should, and has become a growing problem in light of the downward pressure on job tenures over the past decade.1 While many of these left behind 401(k) accounts are ultimately reclaimed, millions of them miss out on higher returns and incur higher-than-necessary fees while forgotten.

Unsurprisingly, many Americans leave their 401(k) behind to deal with later. The result is that job switchers can end up with a string of 401(k) accounts tied to former employers.

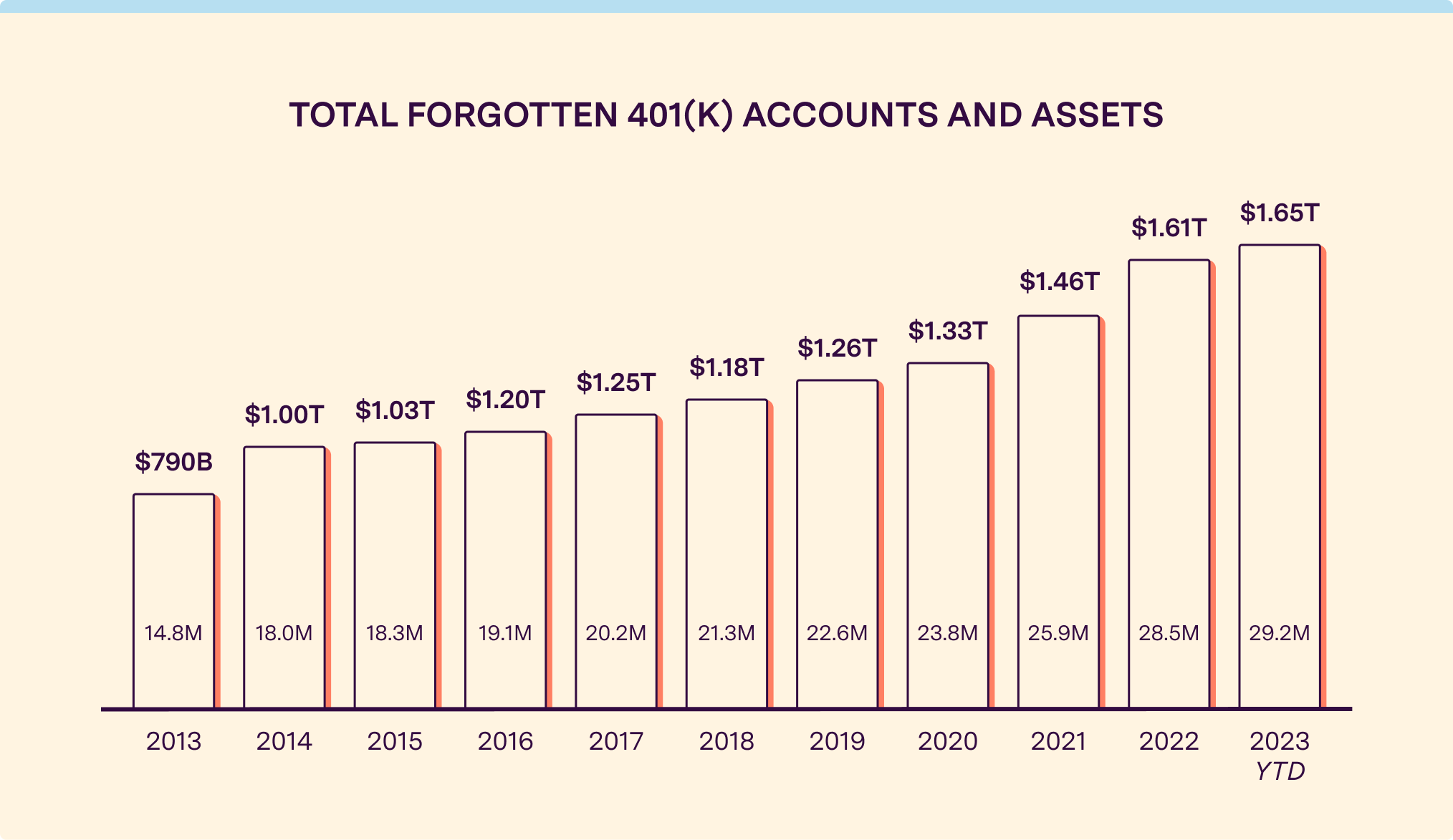

Despite this well-known dynamic, there had been surprisingly little analysis on the magnitude of this problem until our May 2021 white paper. In May 2021, we released the most comprehensive analysis to date of how many 401(k) accounts had been left behind by job-changers and how much they could be costing us. The findings were striking: an estimated 24.3 million 401(k) accounts holding $1.35 trillion in assets had been left behind by job changers as of May 2021 with an average balance of $55,400 in each of these forgotten 401(k) accounts. Our analysis also illustrated the potential opportunity costs of leaving behind money in a poorly allocated, high-fee forgotten 401(k) — up to $700,000 in retirement savings over 30 years to an individual, and $116 billion to retirement savers in aggregate. This analysis was widely cited by the financial media and policymakers.2

Given the volatility in labor & financial markets and legislative developments, we recently embarked on a detailed update to our analysis to incorporate new data, refine our methodology, and share additional insights on the problem.

Our updated analysis shows that size of the forgotten 401(k) problem increased significantly in 2021 and 2022.

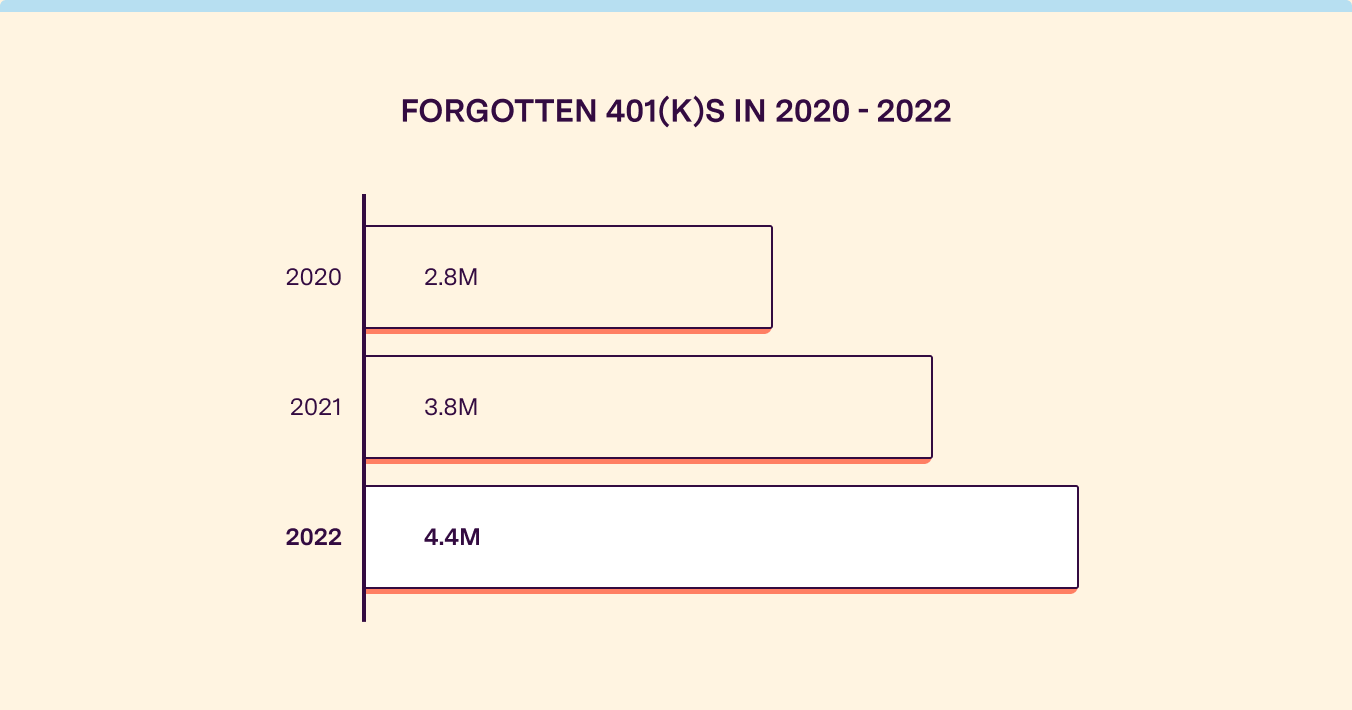

2021 and 2022 witnessed extremely high rates of job switching. “The Great Resignation” induced by a post-COVID employment boom resulted in a record 45 million Americans changing jobs in 2021 and another 47 million in 2022.3

Based on our analysis of BLS data, we estimate that approximately 44% of those job changers had active 401(k)s at the time of transition, which means there were approximately 19.7 million 401(k) accounts “in motion” in 2021 and another 20.8 million in 2022. Of these, nearly 3.8 million were left-behind in 2021 and another 4.4 million in 2022. These numbers suggest that one in five job-changers with a 401(k) left that account behind when changing jobs during 2021 and 2022. The remaining accounts were rolled over into an IRA, a 401(k), or prematurely “cashed out” or withdrawn.4 The 4.4 million accounts left behind in 2022 were nearly 60% higher than the 2.8 million accounts left behind in a benchmark year, as estimated in our May 2021 white paper.

Taking the May 2021 base of 24.3 million forgotten 401(k) accounts, adding in the newly forgotten accounts in 2021 and 2022, and removing the estimated forgotten 401(k) accounts “reclaimed” during this period leaves us with an updated 29.2 million forgotten accounts as of May 2023 — an increase of approximately 20% since May 2021 driven by the elevated rate of job-switching over the past two years. See “Detailed Methodology” below for further details.

While the number of forgotten 401(k) accounts grew rapidly, the average balance in a forgotten 401(k) account increased by a more modest 2.2% to $56,616 from the May 2021 balance of $55,400.

The biggest driver of forgotten 401(k) balances is changes in the prices of equities and other investments that are typically held in 401(k) accounts. With the S&P 500 roughly flat and volatility in fixed income due to interest rate changes, the value of most target date funds has increased very modestly since our last analysis. We use the average balance change of a composite of target-date funds as a proxy for the change in average forgotten 401(k) balances.

As a reminder, our base 2021 estimate used data from the Department of Labor and was refined using summary data from 401(k) recordkeepers on their terminating 401(k) participants, as well as findings from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). See “Detailed Methodology” below for further details.

Putting the numbers together — 29.2 million accounts with an average balance of $56,616 — implies that there’s now approximately $1.65 trillion of assets in forgotten or left-behind 401(k) accounts today. That’s an increase of 23% since May 2021. This $1.65 trillion figure equates to over 25% of all dollars in 401(k) accounts today, and represents a very real but hidden cost of our dynamic labor market.

Over 29 million 401(k)s have now been left behind with $1.65 trillion in assets.

A recent survey revealed that 401(k) fees remain a black box for the majority of Americans:

These fees are not just the investment fees in the account (“expense ratios” on instruments like index funds, or exchange-traded funds) but can often include administrative and advisory fees that are associated with a 401(k) plan and are passed onto savers in those plans. These 401(k) account fees remain material. Updated data from the ICI as of September 2022 shows the median 401(k) fee is 0.79% of assets per year, while the 90th percentile is over 1.4% per year. Not all of these fees will be passed along to savers, but many of them will.

There’s no reason why savers shouldn’t be expected to pay reasonable fees — retirement account providers, whether 401(k) or IRA, incur real cost to manage & administer their products. However, fees in a forgotten 401(k) can be problematic for several reasons:

Even more importantly, the risk of misallocating savings grows as 401(k)s are left behind. While many 401(k) accounts default into target date funds — which automatically rebalance between stocks and bonds as the saver approaches retirement age — millions of them are not in balanced target-date funds and thus rely on the individual participant adjusting their allocations as their financial situations change. This can be difficult at the best of times, but becomes more complex as accounts are accumulated, passwords are forgotten, and financial circumstances change.

Many forgotten 401(k)s under $5,000 are also automatically transferred into “safe harbor IRAs” where they remain in low-returning cash-like investments (such as money market mutual funds). While the yields on these cash-like investments have increased along with interest rates, their returns continue to be significantly lower than the expected returns of a well allocated portfolio of equities, fixed income, and other investments.

A badly allocated, high-fee 401(k) could be missing out on several hundred thousand dollars in foregone retirement savings over 30 years.

The result is that many forgotten 401(k)s are not appropriately allocated in the right mix of investments for the participant. The costs of this misallocation grow with time. Our analysis continues to show that in a worst-case scenario, a badly allocated, high-fee 401(k) could be missing out on several hundred thousand dollars in foregone retirement savings over 30 years. This analysis compares the balance that would accumulate in an optimized retirement account to a lower level of growth in a sub-optimized forgotten 401(k) account that suffers from:

While the math here is illustrative, this risk is not theoretical. Some version of this happens to 401(k) savers every day. The volatile macroeconomic environment only makes effective asset allocation & fee management more difficult and more important. Accepted wisdom on the right long-term split between equities, bonds, and other assets for long-term savers has been called into question (see commentary around the “death of the 60/40 portfolio”). Those who have retirement assets fragmented in multiple accounts have a much smaller chance of actually navigating these transitions effectively.

The potential opportunity cost to savers, collectively, remains sizable. Our analysis continues to show a collective hit to our savings from badly managed forgotten 401(k)s that could be almost $115 billion per year — very close to our May 2021 estimate. While the increase in interest rates has helped increase returns of misallocated 401(k) accounts sitting in cash-like securities — thus helping reduce the return differential & opportunity cost of a badly allocated forgotten 401(k) — the number of forgotten 401(k) accounts has grown to offset this. Almost any way we slice it, this is a significant drain on the retirement savings of our country and a leading but underappreciated reason for our collective retirement savings crisis. See “Detailed Methodology” below for further details.

Layoffs & greater penetration

Job changing isn’t the only driver of forgotten 401(k)s but it is clearly a large one. As we enter 2023, the worsening outlook for the economy & labor market make the prospect of new forgotten 401(k)s all but certain. Job cuts in the first quarter alone totaled over 270,000 — an almost 400% increase from Q1 2022. At Capitalize, we’ve seen first hand the impact of these layoffs as more Americans deal with their 401(k)s after unexpectedly losing their jobs. Unfortunately, this trend is likely to continue as most economic commentators expect recent interest rate increases to eventually result in more job losses.

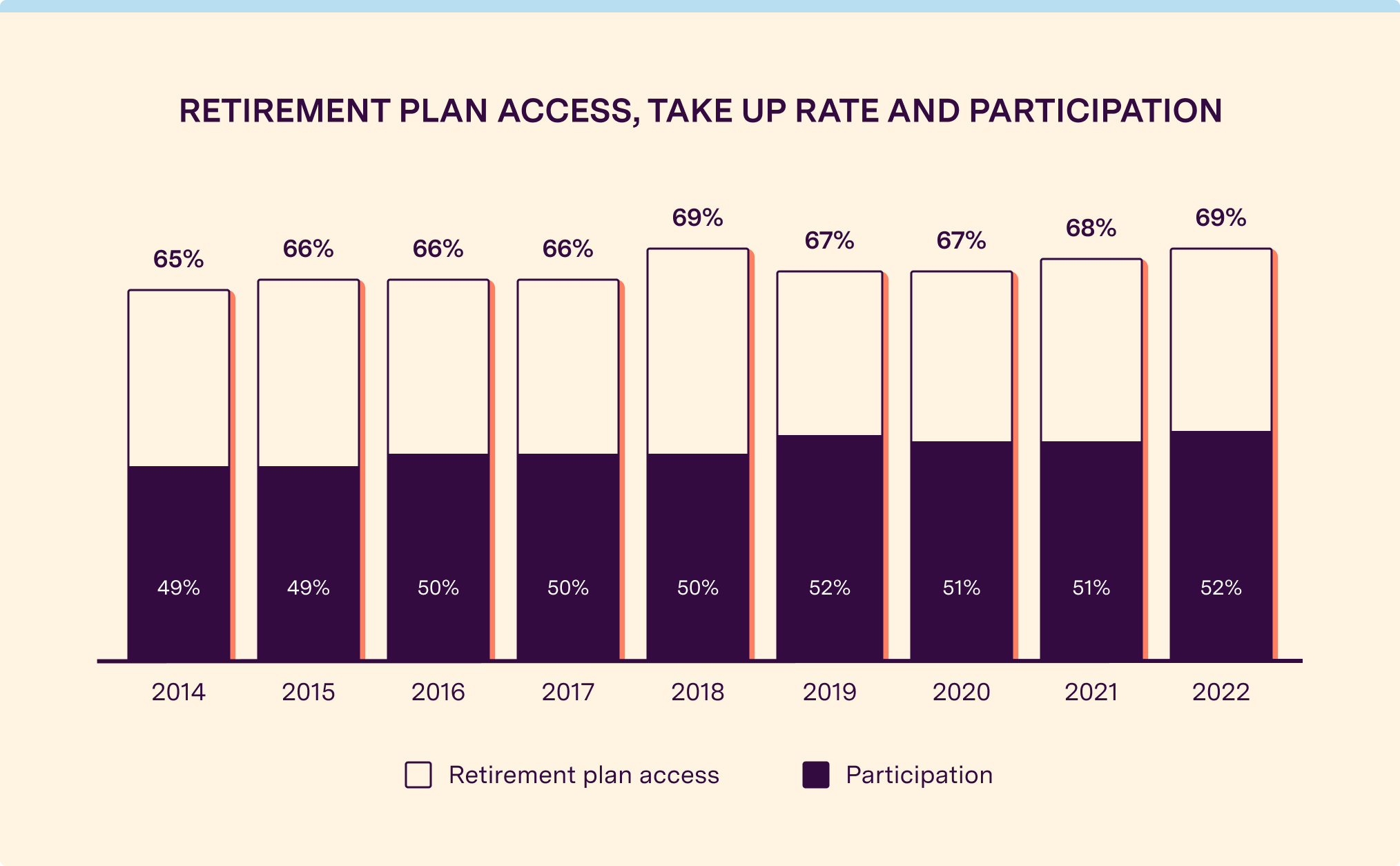

In addition, more 401(k) enrollment — while a good thing — counterintuitively worsens the forgotten 401(k) problem. 401(k) access and usage amongst private sector workers has continued to grow, driven by greater awareness and a more competitive labor market driving up benefits packages. Government incentives have also helped, with the recently passed SECURE 2.0 Act providing coverage for up to 100% of plan administrative costs to small businesses offering a 401(k) plan — up to $15,000 over three years.

More people with 401(k)s is unequivocally good. But with the rate of job switching holding steady or growing over time, the number of left-behind 401(k)s will automatically increase, too. This underscores the importance of solving this problem.

Our updated analysis drew on a variety of sources, databases, conversations with policy experts, and our own estimates where required. We’ve outlined key sources & methodological assumptions here below.

The following sources were critical to our analysis:

The Department of Labor’s Form 5500 database, which leverages annual reporting from employers offering defined contribution retirement plans, serves as the foundation for analyzing the current stock of forgotten 401(k) accounts. According to the latest available data from 2020, there were 23.9 million participants in the “Other Retired or Separated Participants with Vested Right to Benefits” category. This is a helpful starting point to approximate the number of left behind retirement accounts. This number is an estimate and may not account for the full number of accounts, as it does not include some account types (e.g. Solo 401(k)s) and also relies on “historical distribution of retired or separated participants either receiving benefits or with the vested right to benefits,” to arrive at a final estimate, according to the DOL.

We then estimated the growth in this number over the past three years by:

For details of our 2021 White Paper methodology, please see our explanations here.

Our 2021 white paper analyzed data from the DOL’s Form 5500 database, Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), as well as private research sources (e.g. Vanguard) to estimate the average balance for left-behind accounts.

We use this figure as a starting balance, and then we roll forward this balance by analyzing the change in equity value for a composite of major Target Date Funds; we believe this effectively approximates how 401(k) balances have changed since target date funds are a common holding. We took the average return of five Vanguard Target Date Funds from 2018 to 2023 and applied this to our starting balance from 2018.

Note: this number remains well below the average 401(k) balance, reported to be $141,453 as of 2023. For fuller explanation, see our previous research here.

We conducted a scenario analysis to estimate the potential opportunity cost in the form of foregone savings for savers based on a range of assumed returns and fees in 401(k)s.

Our “several hundred thousand dollar” opportunity cost estimate is based on a comparison of what a forgotten 401(k) account would grow to in a well-optimized retirement account vs. a sub optimized account by assuming:

This approach is limited in the sense that there are a wide range of scenarios to consider; many savers’ outcomes may be somewhere in the middle or even outside the range of our estimate depending on account specifics.

Since our May 2021 white paper, we updated our comparative analysis to reflect the increased return from money market funds and other stable value funds from higher rates; while that lowers the opportunity cost of a 401(k) being allocated in one of these vehicles, the potential costs remain high for savers in poorly allocated, high fee portfolios.

| Scenario | Age 35 Starting balance: $55,000 |

Age 45 10 years |

Age 55 20 years |

Age 65 30 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Forgotten 401k in a Money Market – Yearly fees: 0.85% – Annual growth: 2.5% |

$65,848 | $77,556 | $91,346 |

| 2 | Well-allocated, low fee IRA or 401(k) – Yearly fees: 0.40% – Annual growth: 9.2% |

$139,085 | $323,273 | $751,378 |

We’ve made it our mission to help former employees find and roll over their old 401(k)s — and it’s free!

1 Note the decline in median employment tenure across all age groups, particularly the 25-34 demographic down from 3.2 to 2.8 years as of 2022, according to the BLS.

2 As seen in CNBC, Money, Yahoo, AARP, PlanSponsor, 401k Specialist Magazine, MarketWatch, USA Today, and others.

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, JOLTS Database

4 See our “Detailed Methodology” for the full assumptions underlying these estimates. We believe our estimates are well-supported — if not conservative — when considering relevant data points from industry research (e.g. Vanguard’s How America Saves 2022 report which shows 52% of 401(k) participants remain in plan when changing jobs, Alight research on post-termination behavior which shows 26% of 401(k) participants remain in plan when changing jobs, and Pew Charitable Trusts research which shows 24% of 401(k) participants remain in plan when changing jobs)